If people are truly given the right to self-determination, there is a good chance that, in many societies, most will reject the bulk of the (classical) liberal agenda — but isn’t this their right?

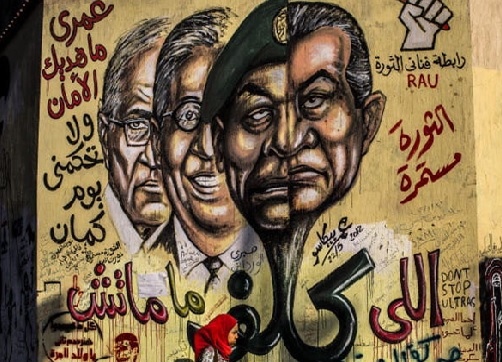

As a case study, consider Egypt. Much has been made over President Muhammad Mursi’s temporary power-grab, of the Islamist dominance in Parliament, and the Islamic flavor of the recently ratified Egyptian constitution. More disturbing, perhaps, is the Mursi Administration’s increasingly “authoritarian” response to continued civil disobedience. While these developments shock liberal sensibilities, it is not clear that they run contrary to the will or interests of the Egyptian people.

While the international media loves to focus on secular, liberal protestors, they are not representative of the general population of Egypt: neither their will, their values, nor their interests. Nor were they responsible for the transition in Egypt; in fact, many of the current protestors against Muhammad Mursi were in favor of the Mubarak Regime. The recent protests have been relatively small; the opposition movement is divided and disorganized; there have been constant counter-demonstrations in favor of the President, sometimes larger than those against him. For years, labor movements and Islamists represented the primary opposition blocs to the Mubarak regime. Accordingly, the narrative that the Islamists “hijacked” the revolution seems problematic.

Egypt is overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim; culturally, the society is very conservative. Consider this: in one of the first scientific polls following the fall of Hosni Mubarak, a plurality of respondents (41.4%) identified Saudi Arabia as their ideal model of government to replace the regime (four times more votes than the runners-up, being the U.S., China, and Turkey, with 10% each). Saudi Arabia, of course, is extremely conservative, religious, and authoritarian; clearly, the will of the Egyptian people seems to diverge drastically from their portrayal on Western media.

These respondents did not get what they wanted, despite electing Islamists to parliament by huge margins – including a number of representatives from ultra-conservative salafist al-Nour party (they ranked 2nd, behind the Muslim Brotherhood; these two parties alone garnered nearly 72% of the total vote). In total, 54% of the electorate turned out at the polls.

In the subsequent presidential election, the illiberal nature of the Egyptian electorate was further underscored. The top two candidates were Muhammad Mursi & Ahmad Shafiq (the latter of whom was the final PM under Hosni Mubarak and ran on a platform to “roll back the revolution” and reinstate order “with an iron fist”). Much has been made of the fact that the two of them, even combined, did not achieve a majority of the vote in the first round of elections (they garnered just over 48%, collectively). But of course, these critics fail to mention that there were thirteen candidates on the ballot from six political parties (and this was after 10 candidates were disqualified), with nearly half of the candidates running as independents (to include Ahmed Shafiq).

Under these conditions, it is actually quite noteworthy that Mursi and Shafiq garnered nearly a quarter of the vote each; they were decisively the top two candidates. And while there was a difference between them concerning the role of religion in the state, neither candidate could be understood as “liberal” by any stretch of the imagination. And this trend is compounded when one also considers the performance of the other illiberal candidates (secular or religious). That is, on the question of liberalism, the message from Egyptian voters was unambiguous, and it was a “no.”

Voter turnout in the presidential election was reduced (compared to the parliamentary elections) down to 46%. This was largely due to the SCAF’s frequent attempts to undermine the democratically elected government, culminating with their dissolution of the Parliament just before the presidential runoff election. This act seemed to backfire: 51% of the electorate turned out to vote in the runoff election (an increase of 5% over the primary), with the Muslim Brotherhood’s Muhammad Mursi winning nearly 52% of the vote. Thereafter, in a bid to defend the elected government against a coup by regime remnants, President Mursi temporarily seized virtually unlimited political powers, which he used to bring the military under control, reinstate the Parliament, and push a constitution to referendum.

This constitution would later be approved by 63.8% of voters; however, only 32.9% of eligible voters went out to the polls. While this abstaining was precisely not a vote to reject (or approve) the constitution, the opposition claimed that the depressed turnout was indicative of the public’s rejection of shari’ah law. On this point, probably the best gauge of Egyptian public opinion is the recent Pew Poll, “The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics, and Society;” in Egypt, more than 90% of the population are Muslims, and Egyptians are significantly more conservative than respondents from other countries: 74% favor making sharia the law of the land; 74% believe sharia should be applied to both Muslims and non-Muslims; 70% favor corporal punishments for crimes such as theft; 81% support stoning as punishment for adultery; 86% endorse the death penalty for apostasy; 75% say religious leaders should have political influence; 55% say Islamist parties are better than other political parties; 94% hold that one must believe in God to be moral.

Clearly, the low public turnout was not driven by popular demand for liberal and secular institutions, underscored by the underwhelming public support for the recent round of protests. It seems more plausible that Egyptians were turned off by the frequent interference of the military, the courts, and outside powers in the formation of the new Egyptian state. The underwhelming public support for the recent round of protests suggests that the issue likely isn’t an overwhelming desire for more secular or liberal institutions. Rather, Egyptians want their government to better represent their values, their interests, and their will. In other words, a government which will further alienate the opposition. In fact, despite the protests, Islamists have won overwhelmingly in every single poll since the fall of Hosni Mubarak and stand well-poised to reclaim their huge majority in parliament in the upcoming elections.

Are the Liberals Democratic?

“It is a general popular error to assume that the loudest complainers for the public to be the most anxious for its welfare.”

Edmund Burke, Observations on a Late Publication on the Present State of the Nation

There is a dramatic difference between working to overthrow a military dictator after decades of rule, and attempting to overthrow a democratically elected president (the first in the country’s history), less than a year after his inauguration, despite the enormous challenges he was immediately faced with. The former is a freedom movement, the latter, sedition (at times, violent).

If a government holds elections, but within a broader state framework which runs contrary to the will, interests or values of the majority of its citizenry — it seems strange to call such a state “democratic.” If said government happened to be liberal, this would not make it more democratic. While the protestors promote themselves as the vanguards of democracy, the essence of democracy is more than a set of (liberal) institutions or occasional election rituals. The essence of democracy is that governments be representative of, and responsive to, the will and interests of the majority of its citizenry. The Islamist-led government seems to fulfill this mandate; the opposition, on the other hand, does not.

And not only does the movement run contrary to the popular will, but also the popular interest. The continued unrest has scared off tourists, foreign investors, and infrastructure development – casting Egypt into an intractable financial crisis, trapping all Egyptians in a cycle of poverty and decline. Should these trends continue, the army may feel “compelled” to dismiss the civilian government altogether and reinstate martial law — thereby obliterating the revolution entirely. Some among the opposition have openly called for this. That is, rather than standing for all Egyptians, these irresponsible actions are bringing ruin upon the entire country. Accordingly, the crackdown on said protests serves to defend rather than undermine democracy in Egypt.

The liberal protesters must acknowledge that compromise is the price of civil society; this means liberals, too, will have to accept things they may not like. They too must submit to laws they strongly disagree with, so long as all Egyptians live under a universal body of laws.

Accordingly, the international community must allow for the emergence of illiberal democracies, or even a popular rejection of democracy altogether, if they are truly committed to promoting the interests and autonomy of the people of the MENA region. To continue to promote these liberal movements at the expense of the popular will and interest — this would be nothing short of cultural colonialism.