U.S. Response in Syria: Digging Deeper Rather Than Crawling Out

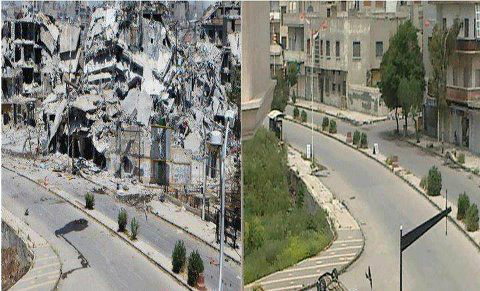

According to U.N. Syria Peace Envoy Lakhdar Brahimi, as the conflict in Syria began to escalate, the U.S. believed that President Assad would be easily driven from power in much the same way as Tunisia’s Ben Ali or Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak. When this quick transition failed to materialize, the U.S. tried to push a Chapter 7 Resolution through the U.N. Security Council, which could have paved the way to forcibly deposing Assad in much the same way they deposed Moammar Gaddhafi. This motion was blocked, in large part because of U.S. overreach of its Libya mandate. This left the Obama Administration with a choice: they could recognize that Assad was likely to stay for the foreseeable future, and help partner with the Syrian government to provide the resources and incentives to help him accelerate the reforms he had committed to, and which were already underway as a result of the protests. Or, they could choose to double-down on their bid to depose him by deepening their support of the rebels. They chose the latter. Following a series of broad defections from the Syrian Arab Army, and the formation of the so-called Free Syrian Army–the Administration established a shadow government, the Syrian National Council, whose cultivation actually goes back at least to 2006 under President George W. Bush. Although these chosen leaders had absolutely no credibility among the Syrian people, they were declared to be the new “official” government in Syria by the U.S. and its allies. These moves helped push the crisis in Syria from a revolt to a civil war. But it was a civil war the government seemed bound to win—the FSA was unable to pose any serious threat to the government and quickly lost anytime they came into direct conflict with them. And so, the Administration was again faced with the choice of rethinking their aspirations in Syria or else escalating their involvement. Again, they chose the latter. In defiance of international rules and norms, which prohibit arming or funding non-state actors against foreign governments, the Administration began partnering with Saudi Arabia and Qatar to provision, arm and expand the Syrian insurgency. It quickly became apparent that most of the weapons provided to the rebels were ending up in the hands of al-Qaeda and affiliated groups who, despite their relatively small numbers, exerted a disproportionate impact over the rebellion. Chief among them was Jahbat al-Nusra, a Syrian franchise of the Islamic State of Iraq—the group now known as ISIL. However, as these fighters began to turn the tide for the opposition, the U.S. remained confident that in the event Assad was deposed, the so-called “moderates” would be able to sweep in and assume control of the state. And they believed such a transition was imminent—the Obama Administration and most analysts, with the notable exceptions of myself and Dr. Landis, declared that President Assad had months at best. Months passed, but the government held on. It ceded without contest a number of areas to the North and West, and consolidated its forces in critical areas while it undertook a restructuring of its chain of command. Then, in the winter of 2012, the Syrian government launched a brutal and effective counteroffensive that began dislodging the rebels from key positions—culminating with their retaking of al-Qusayr. Meanwhile, ISIL had begun setting up their hellscape in rebel-held Raqqa—reports of beheadngs, stonings, crucifixions, and even cannibalism began to trickle into the media. Again, the U.S. was faced with a set of options—they could radically rethink their goals and strategy in Syria, or they could deepen their involvement. The Administration again opted for the latter. Under the pretext of punishing President Assad for the Ghouta chemical weapons incident, the U.S. declared its intention to carry out airstrikes against the government in an attempt to turn the tide. However, as public disapproval became clear, the White House was ultimately forced to abandon the measure. Instead, they increased their efforts to arm, provision and train a “moderate” fighting force. The problem, however, was that there was nobody to equip—from their inception through the present, the FSA and SNC garnered little public support and controlled virtually nothing “on the ground.” In fact, from the available evidence, the rebellion itself was and remains unpopular among Syrians. The most influential forces from the time they entered the theater until the present were al-Qaeda derivative groups. Originally, the al-Nusra Front, then ISIL. ISIL capitalized on the political chaos unfolding in Iraq to seize a broad swath of territory in that country as well—growing vastly richer as a result of their conquests. Ultimately, the extremists began gearing up to threaten the Kurdish capital of Erbil, a critical U.S. oil interest. In response, the White House began a series of airstrikes to push back or redirect ISIL—efforts which have thus far proven to be somewhere between ineffective and counterproductive. Again, the U.S. is being presented with the option to reconsider its approach—and the likely response? Further escalation, and against both Assad and ISIL.