In an administration which has become known for largely continuing the disastrous policies of the previous White House and doubling-down on its own proven failures—President Obama stunned the world with his surprise announcement that the United States would be normalizing relations with Cuba.

The President pointed out that the extraordinary sanctions regime, which has been in place for more than 50 years, has failed at its stated goal of achieving regime change in Cuba. Instead, it has senselessly immiserated the Cuban people for decades. Deeper engagement, he offered, would be the best path forward in bolstering an exchange of ideas between the two countries and promoting mutual well-being. The logic which motivated the Administration to revise its policy on Cuba would seem to apply equally to Iran.

In a recent NPR interview, President Obama left the door open to the possibility of normalizing relations with Iran—however, he insisted (as he has for more than a year) that any such gesture would be contingent on Iran and the U.S. striking a nuclear deal first. But the Administration’s logic here is perplexing considering that a profound diplomatic gesture by the United States would go a long way to convincing Iranians of America’s seriousness in breaking out of the decades of deadlock—helping give President Rouhani the flexibility to overcome the skeptics and hardliners in Iran and close a final deal. Conversely, maintaining America’s adversarial posture in the interim is worse than useless, it’s counterproductive.

Obama should normalize relations with Iran, and he should do it now. He must also find a way to expediently roll back the sanctions in the event of a successful agreement.

Iran Sanctions Originally Intended to Contain Political Islam

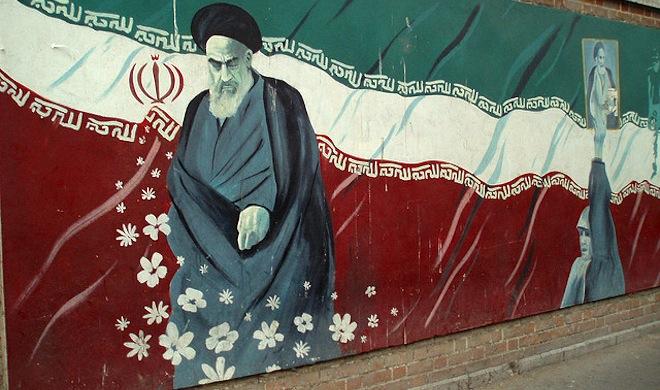

Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the United States became concerned with the spread of Islamism. While the particular expression of the Iranian Revolution was Shia, it had pan-Islamist aspirations and implications. The Iranian revolutionaries called upon believers across the region to join together in casting off the secular dictators and corrupt monarchs who, at that time, ruled virtually every country in the region. Both secularism and monarchism, they argued, ran contrary to Islamic law. Ayatollah Khomeini similarly rejected both liberalism and communism as European constructs which had no future in the Muslim world—instead, he argued, Muslims must derive their own systems of government from their own history, culture, and values.

These ideas electrified the imagination of Muslims, both Sunni and Shia, around the world. However, Washington feared that a successful Islamist country, much like a successful communist regime, could produce a “domino effect.” As the USSR began to decline and collapse, political Islam seemed to be the only force capable of threatening the liberal order–as argued by the likes of Huntington (A Clash of Civilizations), Lewis (The Roots of Muslim Rage), and Fukuyama (The End of History and the Last Man).

And so President Regan tried to contain Iran, economically and geopolitically, to ensure it would not be a “success” others would want to emulate. Meanwhile, it began shoring up alliances with the region’s secular dictators and petro-monarchs, who vowed to stamp out Islamism wherever it reared its head. And so began a dark chapter of U.S. foreign policy, which imploded with the Arab Uprisings of 2010.

In the interim, longstanding U.S. support for autocrats fomented deep mistrust and resentment towards America in the region, exacerbating the problem of terrorism and sparking widespread resistance to U.S. policies in the Middle East. Sanctions on Iran have not prevented the spread of Islamism—instead, America’s alliance with Saudi Arabia has allowed for an unprecedented proliferation of extremist ideology around the world, and helped to foment a sectarian narrative that threatens to tear the region asunder.

Concerns about Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions

Over time, the primary reason for continuing the sanctions shifted to Iran’s alleged pursuit of nuclear weapons.

Ironically, Iran’s uranium enrichment program was actually started by the United States in 1967 as part of the “Atoms for Peace” initiative. And the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT), signed by Reza Shah and subsequently endorsed by Ayatollah Khomeini, affirms it as a right for Iran to enrich uranium for peaceful purposes—unalienable by the United States, the UN or any other external power.

But in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, the Bush Administration began to argue, largely without substantiation, that Iran was working on a nuclear weapon in violation of its treaty agreements. Plans were drawn up for a full-scale invasion and regime change using America’s new forward operating bases in neighboring Afghanistan and Iraq, again under the auspices of “pre-emptive defense”—aspirations which were dashed by the deepening insurgency which bogged down the U.S. military in Iraq. And so instead, in 2007 President Bush pushed through sweeping new sanctions and approved a large covert operations campaign to destabilize Iran.

Since then, America’s own intelligence has unequivocally confirmed that the Islamic Republic has not made the decision to pursue nuclear weapons. For his part, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khameini, has categorically banned the development or use of nuclear weapons. The IAEA has declared that Iran is compliant with the terms of its interim nuclear deal. In fact, the main hang-up in reaching a full agreement is the U.S. insistence that Iran admit that it previously pursued nuclear weapons (a claim which U.S. intelligence has not been able to empirically substantiate)—thereby hoping to justify post-hoc the decades-long campaign against Iran and the utility of sanctions in general.

But in fact, sanctions don’t really work—Iran is no exception to this rule. After nearly 40 years of expanding pressure, Iran is no closer to regime change. Political Islam and Islamic extremism have grown stronger, not weaker—and largely as a result of American attempts to contain Iran, which included supporting secular dictators and petro-monarchs. Iran’s nuclear weapons ambitions cannot be said to have been “curbed” because they cannot be established as having ever existed. Meanwhile, the United States’ allies in Israel and Pakistan have actually developed nuclear weapons, and Saudi Arabia is pursuing them as well—all highly destabilizing actors in the region, facing no sanctions for their nuclear proliferation.

In short, there is no strategic value to the sanctions. They have caused profound and needless misery to generations of Iranians while forcing the Islamic Republic’s leadership into an adversarial position with regards to the United States and the international community. It would be far more productive, both economically and geopolitically, to normalize relations with Iran.

Challenges to Normalization

As with the normalization efforts in Cuba, the biggest obstacle the Obama Administration faces is that, while it has the authority to normalize diplomatic relations, it cannot eliminate most of the significant sanctions without the cooperation of Congress. In either case, the Republican-dominated legislative branch is unlikely to comply with these efforts–especially with regards to Iran, against whom Republicans are actually seeking to expand sanctions further.

For Cuba, the White House will be able to get around some of these problems by declaring that Havana is no longer a “state sponsor of terrorism” in light of the fact that the U.S. counterterrorism focus has been on the greater Middle East rather than Latin America for some time now. This will allow the U.S. to lift the restrictions related to Cuba’s alleged support of terrorists.

This administrative shift would be much more difficult with regards to Iran, which unapologetically provides assistance to groups the United States has classified as terror organizations, namely Hamas and Hezbollah. Accordingly, changing Iran’s designation as a “state sponsor of terrorism” would require also reclassifying those groups, perhaps to “national resistance movements” instead of “terrorist organizations”–a move which is perhaps justifiable and productive for its own sake, but is highly unlikely.

Absent these maneuvers, President Obama has some limited flexibility to unilaterally ease sanctions without Congressional approval, but this would be extremely costly, irreparably poisoning relations with the Republican majority in both chambers of Congress. And so, in all likelihood, diplomatic normalization with Iran would not result in as many immediate economic effects for Iranians as it likely will for Cubans.

There is also concern that these normalization moves, as with all of the President’s executive actions, could simply be reversed in the next Administration. It may be diplomatically awkward to roll back such substantial gestures, but legally speaking, the same rights which empower President Obama to make these reforms would also enable his successor to overturn them.

The trick for the Obama Administration would be to build on these openings with cooperative enterprises that would make such a reversal less palatable for whomever takes the White House in 2016. The nuclear negotiations and the ongoing campaign against ISIL may provide just this sort of opportunity, if Obama is willing to seize it.