In a recent article for the Times Higher Education I pointed out how the lack of ideological diversity among social researchers not only undermines the extent to which research is trusted, funded or utilized, but also undermines researchers’ “capacity to understand phenomena, predict trends, or craft effective interventions.”

Journalistic outlets face many of the same challenges as academic institutions. Like the academy (especially social research fields), most newsrooms skew decisively left. According to the American Journalism project — one of the longest-running and most comprehensive studies of U.S. journalists (conducted every ten years since 1972) — only about 7% of contemporary journalists are Republicans. This is a major decrease as compared to previous studies, suggesting that much like U.S. institutions of higher learning, there has been a significant and fairly rapid ideological shift in newsrooms since the 90s. The American Journalism report also shows that, like the academy, journalism is also suffering a legitimacy crisis driven, in part, by the perceived distance between reporters and the publics they are supposed to serve.

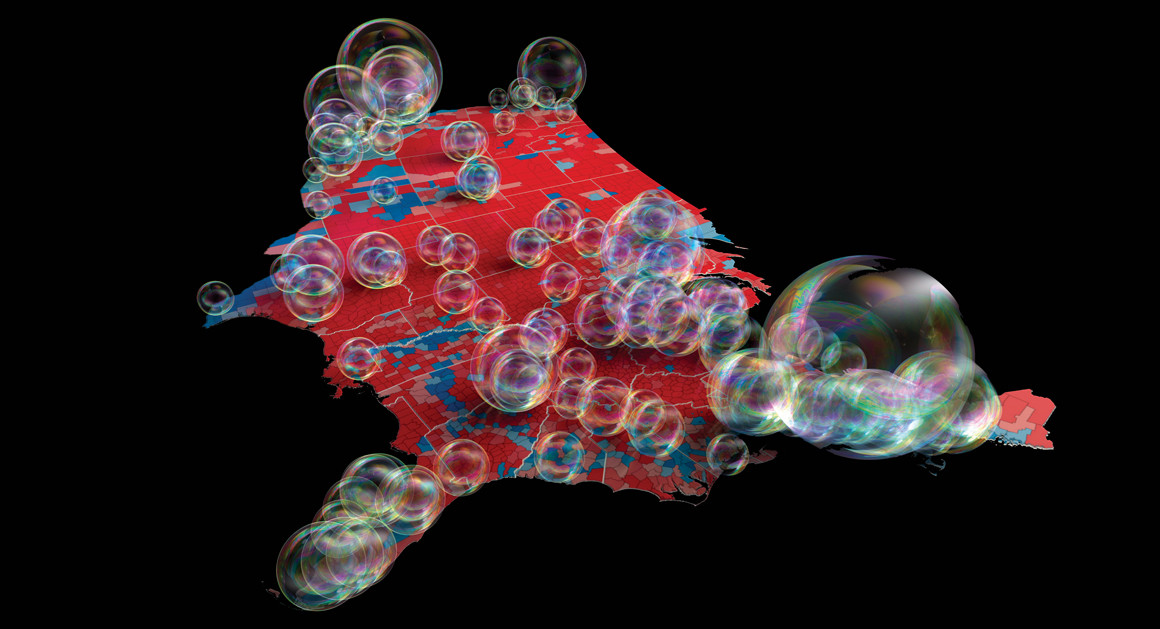

A recent study by Jack Shafer and Tucker Doherty, published by Politico, demonstrates just how vast this divide has grown:

“Where do journalists work, and how much has that changed in recent years? To determine this, my colleague Tucker Doherty excavated labor statistics and cross-referenced them against voting patterns and Census data to figure out just what the American media landscape looks like, and how much it has changed.

The results read like a revelation. The national media really does work in a bubble, something that wasn’t true as recently as 2008. And the bubble is growing more extreme. Concentrated heavily along the coasts, the bubble is both geographic and political. If you’re a working journalist, odds aren’t just that you work in a pro-Clinton county—odds are that you reside in one of the nation’s most pro-Clinton counties…

…The ‘media bubble’ trope might feel overused by critics of journalism who want to sneer at reporters who live in Brooklyn or California and don’t get the ‘real America’ of southern Ohio or rural Kansas. But these numbers suggest it’s no exaggeration: Not only is the bubble real, but it’s more extreme than you might realize. And it’s driven by deep industry trends.”

The authors then go on to explain why the shift is happening. It turns out, the trend seems to be driven overwhelmingly by structural changes to the industry itself rather than by any type of overt or intentional bias on the part of reporters:

“…Internet publishers are now adding workers at nearly twice the rate newspaper publishers are losing them.

This isn’t just a shift in medium. It’s also a shift in sociopolitics, and a radical one. Where newspaper jobs are spread nationwide, internet jobs are not: Today, 73 percent of all internet publishing jobs are concentrated in either the Boston-New York-Washington-Richmond corridor or the West Coast crescent that runs from Seattle to San Diego and on to Phoenix. The Chicagoland area, a traditional media center, captures 5 percent of the jobs, with a paltry 22 percent going to the rest of the country. And almost all the real growth of internet publishing is happening outside the heartland, in just a few urban counties, all places that voted for Clinton. So when your conservative friends use ‘media’ as a synonym for ‘coastal’ and ‘liberal,’ they’re not far off the mark.

This geographical sorting has important implications for the ways contemporary events are understood and described:

The people who report, edit, produce and publish news can’t help being affected—deeply affected—by the environment around them. Former New York Times public editor Daniel Okrent got at this when he analyzed the decidedly liberal bent of his newspaper’s staff in a 2004 column that rewards rereading today. The “heart, mind, and habits” of the Times, he wrote, cannot be divorced from the ethos of the cosmopolitan city where it is produced…The Times thinks of itself as a centrist national newspaper, but it’s more accurate to say its politics are perfectly centered on the slices of America that look and think the most like Manhattan.

Something akin to the Times ethos thrives in most major national newsrooms found on the Clinton coasts—CNN, CBS, the Washington Post, BuzzFeed, Politico and the rest. Their reporters, an admirable lot, can parachute into Appalachia or the rural Midwest on a monthly basis and still not shake their provincial sensibilities: Reporters tote their bubbles with them.”

Unfortunately, as the authors explain in great detail, the structural changes driving these bubbles are likely to persist, or even accelerate, in coming years. So, what can be done to mitigate the sociocultural and epistemic costs of these changes?

Rather than emphasizing a top-down or administrative approach, the authors advocate appealing to journalists’ sense of integrity and pride at getting things right (or shame in blowing a story) to drive them to re-evaluate where they, specifically, went wrong—and what steps might be useful to prevent similar errors in the future:

“The best medicine for journalistic myopia isn’t re-education camps or a splurge of diversity hiring, though tiny doses of those two remedies wouldn’t hurt. Journalists respond to their failings best when their vanity is punctured with proof that they blew a story that was right in front of them. If the burning humiliation of missing the biggest political story in a generation won’t change newsrooms, nothing will.”

Overall, this seems like a constructive approach—one also advocated in the Times Higher Education piece. However, one point of concern remains, namely, the extent to which most reporters actually perceive or acknowledge they did in fact, “blow the story.”

As Nassim Nicholas Taleb has aptly pointed out, prognosticators tend to be great at spinning narratives of how they were fundamentally right about the overall picture, and their model was just thwarted by some act of God, which they need not necessarily atone or account for. Often journalists and analysts are so good at spinning these stories that even when their predictive success rate is abysmally low—especially for major news events—they are nonetheless widely perceived as prescient social observers.

In the aftermath of the 2016 election, many who predicted a Clinton landslide have maintained that they were basically right–but for the last-minute intervention of FBI Director James Comey, Russian propaganda, the surprising strength of third-party candidates, etc. Clinton would have certainly won the Electoral College by a huge margin (after all, she won the popular vote!). In a recent article for The Conversation I demonstrate just how problematic it is to view the 2016 election results as epiphenomenal rather than a continuation of long-running trends. But it remains to be seen how many in the media are, in fact, duly chastened by 2016’s “Black Swan” and what, if any changes they will make going forward.

In the meantime, Shafer and Doherty’s article is packed with useful data, graphics and insights, and mark an important contribution to discussions about the prevalence, causes and costs of ideological bubbles.

Readers should definitely check out the full essay: “The Media Bubble is Real — And Worse Than You Think.”