In mid-July the Edmund Burke Foundation hosted its inaugural National Conservativism Conference – an event intended to “bring together public figures, journalists, scholars, and students who understand that the past and future of conservatism are inextricably tied to the idea of the nation, to the principle of national independence, and to the revival of the unique national traditions that alone have the power to bind a people together and bring about their flourishing.”

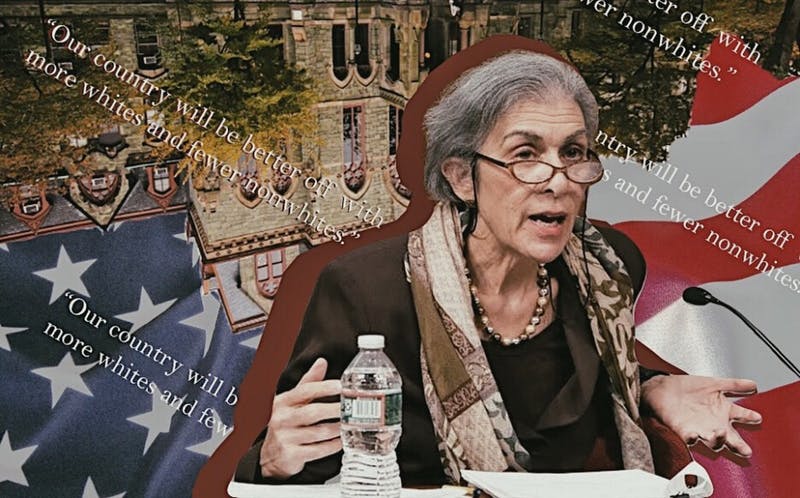

One of the speakers at this conference, University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax, generated national headlines for her talk at this conference, which was based on one of her recent publications in the Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy, “Debating Immigration Restriction: The Case for Low and Slow.”

In her remarks (transcript available here), Wax argued that the United States would be “better off if our country is dominated numerically, demographically, politically, at least in fact if not formally, by people from the First World, from the West, than by people from countries that had failed to advance.” Embracing this ‘cultural distance nationalism,’ she continued, would be tantamount to “taking the position that our country will be better off with more whites and fewer non-whites” – but conservatives should rally around it nonetheless, rather than shrinking away from the ‘best’ policy for fear of being branded as xenophobic or racist.

In many respects, her comments at the National Conservativism Conference echoed (and built upon) a previous op-ed she co-authored, “Paying the Price for Breakdown of the Country’s Bourgeois Culture,” published by The Philadelphia Inquirer in August 2017.

In that essay, Wax and her co-author argued, “All cultures are not equal. Or at least they are not equal in preparing people to be productive in an advanced economy.” Anglo-Saxon Protestant bourgeois cultural norms, they argued, are better than virtually all competing alternatives, and we denigrate or move away from those social mores at our peril. In a subsequent interview about the essay and the controversy it spawned, Wax elaborated, “I don’t shrink from the word, ‘superior’… Everyone wants to go to countries ruled by white Europeans.” Minorities could “get ahead” in America, she continued, if only they abandoned their ‘inferior’ cultural values and practices in favor of her own.

Many derided these comments as empirically troubled and bordering on white supremacist – leading to an open letter condemning her remarks, signed by dozens of her UPenn colleagues.

Wax set off a new firestorm mere weeks later for asserting in an interview with Brown University economist Glenn Loury that, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Black student graduate in the top quarter of the class, and rarely, rarely in the top half … I can think of one or two [black] students who scored in the top half in my required first year course.”

These remarks led to widespread calls for her dismissal. The dean of University of Pennsylvania Law, Theodore Ruger, publicly disputed the accuracy of her claims about black student performance and announced that she had been indefinitely barred from teaching mandatory first-year courses as a result of her comments.

Wax’s latest comments were also condemned by Dean Ruger – and she is once again facing calls for her ouster as a result of making comments many interpret as white supremacist in nature.

Many have described Wax’s latest controversy as a difficult case on academic freedom and its limitations. It’s not. Tenure and academic freedom, as we currently understand them, were literally created in response to another prominent scholar’s getting canned for making inflammatory statements on race and immigration. That scholar was Edward A. Ross, and many of those troubled by Ross’s firing personally rejected — and even publicly repudiated — his views. Understanding why they nonetheless rallied in support of his academic freedom can provide important insights into the Wax controversy today.

The 1900 Stanford Incident and the Creation of Tenure

In the late 19th century, Edward A. Ross was a pioneer in the fields of sociology and criminology and a professor at the nascent Stanford University. He was, like Wax, one of the most prominent scholars in his field. He also seemed to share a number of Wax’s views with respect to race and immigration.

He believed that whites were — in virtue of their culture and circumstances — superior to others. He held a restrictionist view on immigration. Ross was particularly averse to migrants from China and Japan, arguing that accepting large numbers of people from these countries would be tantamount to “race suicide” for whites — which would lead to America’s cultural, moral, economic, and geopolitical decline.

He frequently made his case at public events and, like Wax, often sought to provoke. At one such talk, he allegedly proposed, “Should the worst come to the worst, it would be better for us if we [the United States] were to turn our guns upon every vessel bringing Japanese to our shores rather than to permit them to land.”

When these comments were reported in a local newspaper, Jane Stanford called for Ross to resign or be terminated. When a colleague protested Ross’ sacking, she fired him too. This led to a wave of resignations from other university faculty in protest of Mrs. Stanford’s perceived overreach – sparking perhaps the first major national public controversy about free speech, politics and the Ivory Tower.

The incident also spurred a wave of academic activism:

Columbia University philosopher John Dewey was particularly troubled by Ross’ termination – and began to publicly argue that professorial autonomy should not be contingent upon the whims of people who administer academic institutions. He rallied other professors to his cause — starting with those who were terminated or resigned in the 1900 Stanford Incident – eventually leading to the 1915 formation of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP).

Dewey served as the association’s first president. The top priorities of the organization were to render tenure protections more robust, to help standardize tenure processes and protections across disciplines and institutions, and to ensure that professors (rather than administrators or trustees) played the central role in decisions to hire, promote or dismiss faculty members.

These efforts culminated in the landmark 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure — jointly formulated with the then-fledgling American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) – which has come to define academic tenure in the United States ever since.

Academic Freedom and Its Limits

Dewey started a national movement to prevent what happened to Ross from happening to other scholars. This was not because he shared Ross’s eugenicist and restrictionist views — he didn’t.

Dewey believed that all people were biologically equal. Although he viewed some groups as having cultural and technological advantages over others (as a result of historical contingencies), he was committed to closing these gaps. He consistently advocated on behalf of African Americans, particularly with respect to increasing access to early childhood education – and likened racism to a “social disease.” In a 1922 essay, “Race Prejudice and Friction,” he explicitly repudiated the anti-immigrant and anti-Asian sentiments espoused by Ross and his fellow travelers.

Nonetheless, Dewey was troubled by Ross’s termination because he recognized that it was dangerous for all academics — and harmful to the production of knowledge — if trustees, administrators, or public mobs were able to wield arbitrary power over professors.

In his view, faculty members should be able to follow the facts as they understand them, wherever they lead — and describe the world as they see it — even if it runs sharply against the ideological and political sensibilities of the people who run the universities, even if it cuts against trustees’ or donors’ material interests, even if the positions being advanced are unpopular with other academics or the public at large. Indeed, it is precisely in these instances where academic freedom matters most.

The protections originally built in response to Ross’ sacking were later evoked to defend socialist and communist professors during the ‘Red Scare.’ They were also central to civil rights activists on campus, and for the establishment of fields like African-American Studies. Opponents then (as now) called for this work to be suppressed on the grounds that challenging white supremacy, in practice, amounted to fomenting racial hatred and division and providing support and legitimization for ‘extremist’ views.

When the Temple University media professor Marc Lamont Hill argued for a “free Palestine from the river to the sea” during a speech at the United Nations, he was accused of calling for the destruction of Israel. There were calls for his termination — a Temple trustee called these remarks “hate speech” and declared his intent to punish Hill. However, Hill was ultimately saved by the same tenure protections Wax is relying on today.

Many others are not so fortunate. In this sense, Wax’s critics have the issue precisely backward: The problem is not that Amy Wax is protected by tenure. The problem is that most other academics, especially women and scholars of color, don’t enjoy comparable protections.

That is, rather than trying to find ways to circumvent Wax’s protections — which could make it easier to terminate left-leaning scholars on political grounds as well — we should instead be working to shore-up and expand tenure to include an even broader swath of the intellectual community. We should be working to complete Dewey’s project rather than dismantle it.