Isaac “Ike” Lambert was a decorated detective who had served more than 24 years in the Chicago Police Department. In 2017, an off-duty officer shot a teenager named Ricardo Hayes, who had autism and whose caregivers had reported him missing hours before. Some officers then tried to charge Hayes with assault on the basis of a distorted police report. Lambert noticed that his colleague’s official narrative of the encounter was sharply at odds with eyewitness accounts and other evidence (including video of the incident). Lambert declined to press charges against Hayes, then repeatedly refused to sign off on the officers’ fraudulent report—despite higher-ups insisting he help bury the incident. For this, Lambert was promptly “dumped” to patrol duty.

In a case like this, an understandable inclination would be to focus on the victim, an unarmed autistic kid who had committed no crime — or on punishing the police officer who assaulted him. (Officer Khalil Muhammad received a mere six-month suspension for shooting Hayes.) Lost in the discussion are principled officers like Lambert, who resisted attempted malfeasance by his colleagues and paid a price for it.

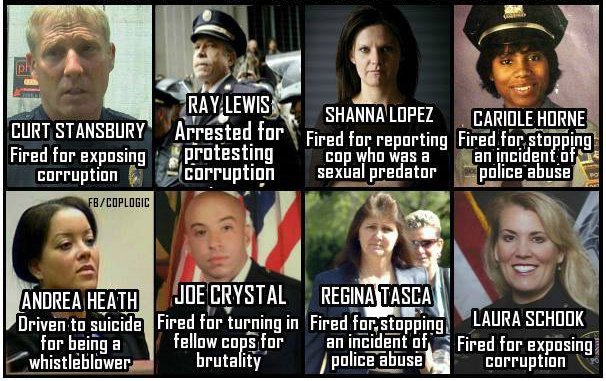

He is far from alone. Police officers in the United States engage in all manner of bad behavior, such as excessive force, sexual misconduct, financial impropriety, and the manipulation of evidence. Holding them to account criminally, civilly, or professionally is extremely difficult, even in cases involving blatant malpractice and misconduct. Yet, even as bad cops evade punishment for wrongdoing, those who stand up to corruption, report negligence or abuse, or decline to comply with bad orders are frequently marginalized, demoted, or outright fired.

In May 2016, Stephen Mader, a police officer in Weirton, West Virginia, responded to a call by a distraught woman who said that her boyfriend, R. J. Williams, was threatening to harm himself with a knife. According to subsequent reporting on the case by ProPublica, she mentioned that Williams had a gun, but that it was unloaded, and she urged the police to intervene to save his life. When he arrived at the scene, Mader, a former marine, quickly surmised that Williams was not a threat and was trying to commit “suicide by cop.” He tried to talk Williams down, and was making progress—that is, until two other officers arrived on the scene and quickly shot Williams in the head. When officers inspected Williams’s gun, they found it was unloaded, as was indicated in the call to dispatch. Rather than sanctioning the other officers for using unnecessary force against someone with a weapon that they had been told was unloaded—for killing the very person they had been called upon to help—Weirton police fired Mader for exercising restraint. By failing to immediately shoot Williams, his superiors argued, he’d jeopardized his own life as well as the lives of his peers and any civilian bystanders. Mader sued for wrongful termination and ultimately settled for $175,000. However, he was not able to get his job back. He worked for a while as a truck driver before joining the National Guard, where he is now a military police officer.

In 2013, police officers in Auburn, Alabama, were assigned by their supervisor to a monthly quota of 100 “contacts”—that is, arrests, traffic tickets, warnings, and so on. Given how many officers there were on the force, meeting this standard would have entailed 72,000 contacts per year in a relatively quiet town with a population of just over 50,000. Officer Justin Hanners spoke out against the policy, arguing that cops should interfere with people’s daily lives as little as possible, and only when they were needed. He insisted that the role of police should be to serve and protect, not to shake down civilians for money. For expressing his opposition to quotas and refusing to comply with them, Hanners was fired. (Auburn police officials insisted they had imposed no quota, but Hanners produced recordings that appeared to back up his contentions.) Hanners filed a wrongful-termination lawsuit against the city of Auburn; it was dismissed partly on the grounds that, as a municipal employee, his whistleblowing actions were not covered by Alabama’s State Employee Protection Act. In the aftermath, unable to pay the bills, Hanners was forced to spend most of his retirement savings on keeping his family afloat. They ultimately lost their home to foreclosure and had to move in with relatives.

By 2006, Officer Cariol Horne had put in 19 years for the Buffalo Police Department. Shortly before her scheduled retirement, she arrived at a crime scene to find a fellow officer choking a handcuffed Black man while her fellow cops stood idly by. By her account, she urged the offending officer, Gregory Kwiatkowski, to stand down, because the situation was under control and the suspect was not a threat. Her pleas were ignored. Worried that Kwiatkowski, who is white, was about to kill the man, she pulled her colleague’s arm from around the suspect’s neck. In a rage, Kwiatkowski punched Horne in the face, damaging her teeth. The suspect was taken into custody. Afterward, rather than punishing Kwiatkowski for choking a handcuffed man and then assaulting another officer, Buffalo police fired Horne for obstructing justice. (No other officer backed up her account, and Kwiatkowski successfully sued her for defamation.) She was denied her pension, and has been unable to retire. Instead, to pay the bills for herself and her three sons, she has been working as a driver—of semis, school buses, rideshares. She has often struggled to pay rent, and even had to live in a shelter for a while.

The decision to punish Horne, not Kwiatkowski, proved fateful. According to ABC7 Buffalo, he would go on choke another officer on the job, and in a separate incident, punch still another officer while off duty. Yet he remained on the force. In 2009, he was caught slamming four Black teenagers into the ground, then punching them and berating them as “savage dogs.” Once again, his victims were already handcuffed. Kwiatkowski eventually pleaded guilty to using excessive force in this incident. According to The Buffalo News, during his trial Kwiatkowski also admitted to having “lied several times in the past about using excessive force, including under oath in both a civil trial and an Internal Affairs investigation.” He was ultimately sentenced to a mere four months in jail for his crimes—roughly a decade after the 2009 incident. Unlike Cariol Horne, he was allowed to retire from the force and keep his pension.

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, many have demanded to know how the other Minneapolis officers captured on camera could have stood around with their hands in their pockets for eight minutes and 46 seconds, while Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on a man’s neck. Cariol Horne’s saga, and others like it, help explain why. The system protects cops like Chauvin, who had at least 17 previous misconduct complaints —including multiple claims of excessive force, repeated uses of lethal force, and previous referral to a grand jury for possible criminal prosecution for a previous incident. However, cops who exercise restraint (in the case of Mader), stop others from engaging in brutality (like Horne), prevent officers from concealing wrongdoing (like Lambert), or blow the whistle on bad police practices (like Hanners)—they are often immediately and severely sanctioned or pushed out, both through formal and informal means. This is perhaps one of the most significant yet largely neglected problems with policing in America: Instead of being held up as a template for others to follow, the system often ‘makes an example’ out of ‘good apples’ like Lambert, Mader, Hanners and Horne.

Yes, we need better ways to identify and purge bad cops and should —including addressing union arrangements that often force departments to rehire ‘bad apples’ they’ve tried to force out — and make sure that, when fired, these cops cannot simply move to another precinct and spread corruption elsewhere. Yes, we should be talking about ways we can restructure law enforcement to reduce violent encounters. But police departments also need better protections and incentives for those officers who prioritize their sworn duties above loyalty to their peers or their own personal well-being. This is underdiscussed, but crucially important. If bad cops get off while good cops get axed, Americans should not be surprised when officers who know of wrongdoing by their colleagues stand aside and let it happen – allowing malefactors to exert disproportionate influence over the system and how it functions.

7/5/2020 update: Just days after this story was published, Springfield PD detective Florissa Fuentes was fired for sharing a story on Instagram of her niece participating in a Black Lives Matter protest. Meanwhile, hundreds of officers have been confirmed to be participating in online Facebook hate groups. Most have not suffered consequences, despite their precincts being made aware of these behaviors.

Indeed, according to a separate investigation by Injustice Watch, of the departments surveyed, 1 in 5 active duty cops, and 2 in 5 retired cops, made online posts “displaying bias, applauding violence, scoffing at due process, or using dehumanizing language.”

In a perfect illustration of the phenomenon discussed in the essay above, a cop supportive of racial justice was fired for her online activities even as those regularly engaging in online racist behavior are protected (despite rules in many precincts explicitly forbidding officers to engage in online forums in ways that suggest prejudice or bias along demographic lines).

Indeed, Fuentes was fired for supporting protests calling for police reform *on the internet.* Meanwhile, many officers have been documented assaulting these protesters without cause *in real life* without facing meaningful consequences.

Again, too often the system punishes good cops for trying to do the right thing, even as bad cops regularly avoid punishment — even for grievous malpractice and misconduct. Until this changes, the ‘bad apples’ will continue to exert an outsized influence over policing in America.