Democrats Went “All In” on Knowledge Economy Professionals. They Have Not Returned the Favor.

Starting during the period the World Wars, and accelerating during the 1970s, there were important shifts to the global economy that favored professionals who work in fields like law, consulting, media, arts, entertainment, finance, education, administration, science and technology – folks who traffic primarily in data, ideas, rhetoric and images instead of physical goods or services. After 2011, there were massive shifts in how these knowledge economy professionals talked about and engaged in the social world. This period of rapid change came to be known as the “Great Awokening.”

Over the course of the Great Awokening, the kind of people who make up the knowledge professions aligned themselves much more closely with the Democratic Party. The party, in turn, reoriented its messaging, candidates, platform, and priorities around knowledge-economy professionals. One could see how this might have seemed like a good bet at the time: These professionals are passionate about politics. They vote, donate, and advocate consistently and intensely. They have a lot of clout in society, and they appear poised to grow only more influential for the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, from our contemporary vantage point, it seems as if it may have been a disastrous political miscalculation for the Democratic Party to go “all in” on knowledge economy professionals.

The core problem the Democrats face in trying to build a political coalition around knowledge economy professionals is that, compared to most other voters, they – we – tend to be really strange.

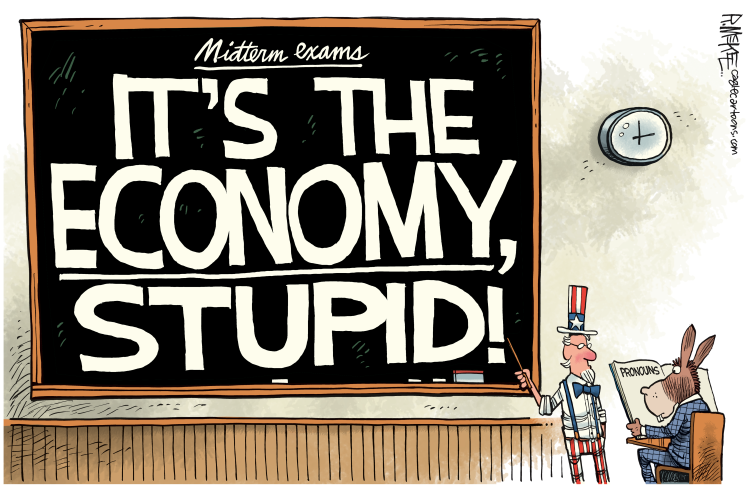

For instance, the types of people who comprise the knowledge professions tend to be far more ideological and extreme than most other voters. Because our lives and livelihoods are oriented around symbols, we tend to take idiosyncratic struggles over things like language, status and representation very seriously – to the point of crowding out more practical issues that normie voters care most about. We are much more likely to engage in “political hobbyism” and “expressive politics”– engaging in political action and discourse for the sake of self-expression or entertainment instead of working towards concrete or material goals. We are also far more likely than others to derive meaning in our lives from political participation than most other Americans.

With respect to values, most in the U.S. skew ‘operationally’ left (i.e. favoring robust social safety nets, government benefits and infrastructure investment via progressive taxation) but trend more conservative on culture and symbolism. For instance, they tend to support patriotism, religiosity, national security and public order. Knowledge economy professionals tend to be oriented in the exact opposite direction: we skew culturally and symbolically ‘left’ but favor free markets.

Even in cases where our interests and values overlap with the general public, the ways we like to frame issues tend to be alienating to most other voters. For instance, most Americans prefer policies and messages that are universal and appeal to superordinate identities over ones oriented around specific identity groups (e.g. LGBTQ people, women, Hispanics, Muslims). They tend to be alienated by political correctness and prefer candidates and messages that are direct, concise and plainspoken. They prefer people who focus on positive and inspiring visions of what America was, is and could be instead of focusing relentlessly on the negatives. They prefer people who are charismatic, religious, successful, moderate and conventionally attractive over “wonks,” “technocrats,” ideologues and eccentrics. Knowledge economy professionals tend to have preferences that run contrary to everyone else in each of these domains.

As a result of these types of disconnects, it’s hard to have a party that appeals strongly to knowledge-economy professionals and “normies.”

Recent data from Gallup underscore this point powerfully. When we look at which constituencies in America identify with the Democratic Party today, we can see that, basically, it’s knowledge-economy professionals: folks with a bachelor’s degree or higher; women (who comprise a large and growing majority of Americans who receive college degrees and staff the knowledge professions); people who live on the coasts and in big cities or suburbs; people who don’t participate in organized religion (highly educated white liberals are increasingly abandoning religion, even as people of non-Christian faiths have been shifting increasingly “right” alongside Christians).

Nonwhites continue to lean Democratic, to be sure. However, the party has seen consistent attrition among people of color since the outset of the Great Awokening. Black identification with the Democratic Party seems to have peaked in 2008, with consistent declines ever since—accelerating dramatically after the onset of the post-George Floyd “racial reckoning.” As Democratic members of Congress took a knee in matching kente-cloth stoles when introducing the “George Floyd Justice in Policing Act” (which, by the way, they couldn’t actually enact), black voters began moving away from the Democrats at an accelerated rate.

Likewise, when candidate Joe Biden picked Kamala Harris as his running mate—America’s first black, South-Asian and female vice-presidential nominee—he presumably hoped this would shore up support from these groups. Instead, Democrats did worse in 2020 with black people, Asians, women, and black women in particular. Harris added nothing to the ticket in 2020 (and may well be a liability in 2024, given growing concerns about Biden’s age and Harris’ own lack of charisma).

The Biden Administration made a number of historic appointments, including America’s first black female White House press secretary and Supreme Court justice. Workaday Democratic politicians began invoking “systemic racism.” The White House vociferously defended controversial DEI initiatives (and created many new ones). The party and its boosters never missed an opportunity to characterize Trump and his supporters as racist and to warn of dire consequences for people of color if the GOP were to gain power.

Democratic Party officials may have believed these symbolic measures could appeal to professionals while also shoring up support with nonwhite voters, thereby stitching the “Obama coalition” back together. Unfortunately for them, “anti-racism,” as typically understood and operationalized by knowledge-economy professionals, does not well reflect the preferences and priorities of most nonwhites. Instead, they tend to alienate “normies” across racial and ethnic lines.

Indeed, the Democratic Party is hemorrhaging support among many other groups besides black Americans. The same patterns are visible among Hispanics and Asians. These trends were evident in the 2022 midterms (Democrats avoided a ‘red wave’ largely due to favorable shifts among relatively affluent whites, especially white men, despite continued erosion among women and minorities). Gallup’s data suggest the trends seem likely to persist through the 2024 election cycle, as well.

This erosion of Democratic support among “normies” across racial and ethnic lines would present a challenge for the party even if they managed to sustain or enhance their performance with knowledge-economy professionals indefinitely. However, the party may be facing an electoral crisis in 2024 because the Great Awokening seems to have run its course and, as a consequence, many knowledge-economy professionals feel freer to emphasize their support for free markets instead of voting purely on cultural issues. And their identification with the Democratic Party has softened in turn.

Although the Great Awokening is often discussed by conservatives in terms of “kids these days,” as I detail at length in my forthcoming book, periods of rapid symbolic change around “social-justice” issues in America have been driven primarily by early-to-mid-career professionals instead of young people and the genuinely disadvantaged.

In Gallup’s data, we can see that after 2011, Americans under 30 shifted firmly towards the Democratic Party. Their alignment seems to have peaked in 2016, with consistent declines since. Contemporary support for the Democratic Party among young adults is now at its lowest levels since 2005 (rest in peace, “emerging-Democratic-majority” thesis).

Americans between ages 30 and 49 began shifting towards the Democrats a year earlier and peaked two years later (in 2018). Today, Democratic support among middle-aged adults is the same as it was before the Awokening. All the gains have been washed away.

Women play an increasingly central role in the knowledge professions, and gender plays an important (and in some respects, under-analyzed) role in cultural contestation around knowledge-economy institutions, agents, and outputs. American women shifted hard toward the Democratic Party after 2010. However, female identification with the party seems to have peaked in 2018 and is currently hovering around pre-Awokening levels.

Almost all knowledge-economy professionals have a college degree, and degree holders overwhelmingly (and increasingly) aspire towards white-collar professions. We can see the rise and decline of the Awokening clearly among voters who’ve completed college.

After 2011, bachelor’s degree holders went from being the least Democratic educational bloc to the second most Democratically aligned (exceeded only by postgraduate degree holders). However, BA holders’ identification with the Democratic Party seems to have peaked in 2020 and has declined consistently since (although BA holders still remain much more closely aligned with the Democrats than Americans who have not completed college, and they continue to identify much more strongly with the Democratic Party than they did before the Awokening).

Shifts among postgraduates seem to have started a year earlier (after 2010) and peaked a bit earlier (in 2018). Critically, however, the identifications of Americans with graduate degrees simply leveled off after 2018, rather than shifting away from the Democrats. Nonetheless, this stagnation is still a problem, because it means Democratic losses with other educational blocs have not been offset by growth anywhere. Instead, Biden has faced consistent declines in his popularity across almost all divides. As I write, his net approval rating is lower than all other presidents on record (since 1945), including Trump’s at the same point in his administration.

If the 2024 election goes the way it’s trending to go, there will be innumerable takes in the aftermath about how Trump was ushered back into power as a result of white supremacy, sexism, and other retrograde prejudices. A more realistic, albeit less satisfying, answer is that the Democratic Party went “all in” catering to the cultural preferences of knowledge-economy professionals after 2010 in ways that alienated most other voting blocs, including poor and working-class people and minorities—the very “marginalized and disadvantaged” populations that “social-justice” advocates often purport to champion. This approach seemed to bear fruit while cultural issues were highly salient for educated professionals (although Democrats saw consistent attrition in their support among most other subsets of society, trends that were readily apparent in 2016). However, the post-2011 culture wars couldn’t dominate the American political landscape forever.

For instance, contrary to “the discourse,” the last four years have actually been pretty good for most workers. Unemployment is near record lows. Inflation is under control, and wages have risen faster than prices for most workers. Socioeconomic inequality is down. However, as Shamus Khan emphasized, the socioeconomic prospects of elites tend to operate countercyclically to those of everyone else. Although the last four years have been relatively solid for workers, they haven’t been great for the upper-middle class and wealthy people who dominate the knowledge professions. And as professionals began to chill out a bit on cultural issues, they grew more open to voting for the party of tax cuts and deregulation.

The Democrats, having hollowed out their traditional base in a vain attempt to secure the enduring allegiance of these professionals, now face a borderline unworkable coalition. They stand poised to lose the popular vote for the first time in two decades in spite of the fact that Biden’s most likely opponent is deeply unpopular himself, seems increasingly deranged and vindictive, has already been impeached twice, is currently facing myriad civil and criminal investigations, and was decisively voted out of office in the last election.

It would be quite an accomplishment for a sitting incumbent to lose to a candidate with such extreme liabilities while presiding over a strong economy. But the Democrats seem poised to achieve this extraordinary feat—a testament to how badly they miscalculated in reorienting the party around knowledge-economy professionals in the midst of the Great Awokening.