Tenured and tenure-track college professors are drawn from a narrow and idiosyncratic slice of society. Many backgrounds and perspectives are dramatically underrepresented in the academy. This gulf between the ivory tower and the rest of society undermines knowledge production, pedagogy, and public trust in experts and scientific claims.

A new study published in Nature Human Behavior argues that, at its current rate of change, the faculty will likely never approximate parity with the broader U.S. population. The paper did not provide a deep dive into why, specifically, the faculty remains so unrepresentative. Nor did it provide a road map for efficiently closing the gaps. This essay will dive into those questions.

However, let’s start by establishing some baselines with respect to how the faculty is composed today.

Who Are Professors?

In chapter 2 of my forthcoming book, I marshall statistics from the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI), Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), and other sources to sketch out the composition of the U.S. professoriate. Professors, I argue, are in many respects illustrative of the broader gap between knowledge economy professionals and the publics they ostensibly serve. Many other “knowledge” fields, such as journalism, law, consulting, tech, and finance, are similarly parochial, to the detriment of aligned institutions and American society more broadly.

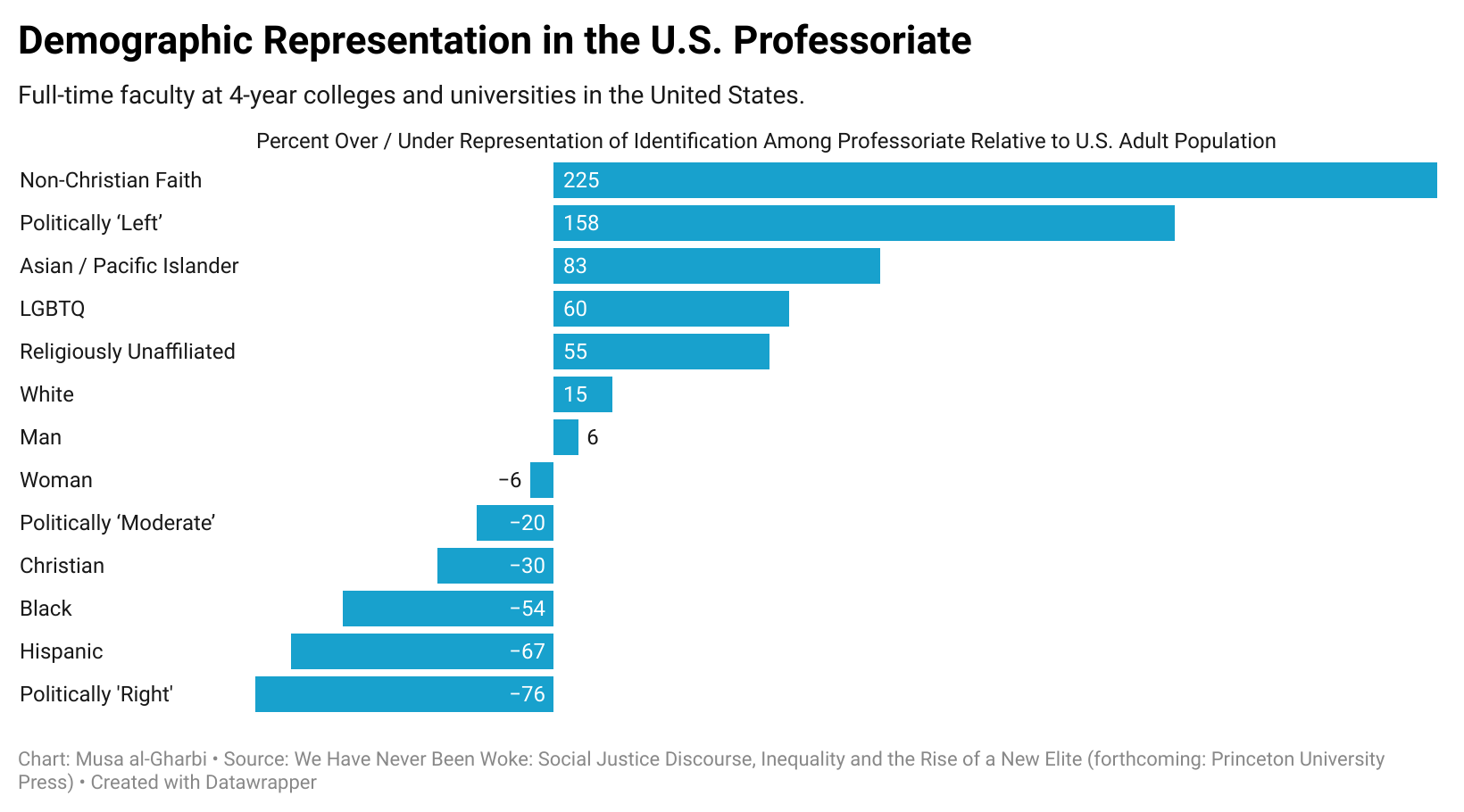

Here is a chart from the text, comparing the demographics of U.S. full-time faculty with the broader adult population (see here for additional information on the provenance of these data).

We can see that in terms of raw percentage point gaps, the most overrepresented groups seem to be people on the ‘left’, the religiously unaffiliated and whites. The biggest underrepresentation gaps, looking at raw percentage points, are for Christians, people on the ‘right’ and Hispanics.

In addition to looking at absolute percentage point gaps, we can also visualize this data as a series of ratios. This would allow us to see more clearly which groups are the most over or underrepresented relative to their baselines in the broader society (and allow us to better normalize comparisons across different categories):

For a host of reasons, it would be difficult to include the socioeconomic backgrounds and the community types (rural, urban, suburban) that faculty were typically raised in within these same charts. However, an ambitious recent study exploring the socioeconomic backgrounds of faculty members found that nearly 9 in 10 professors have grown up in urban areas; on average they enjoyed household incomes that were 23.7% higher than the national average at the time of their childhoods. More than 3 out of 4 grew up in houses their parents owned (also higher than national averages during their childhoods). Most faculty had at least one parent with an advanced degree; nearly three-quarters had a parent with at least a B.A. Moreover, the authors found, those raised by one (or more) parent with a Ph.D. were significantly more likely to land a tenure-track position at an elite school as compared with faculty whose parents did not have terminal degrees.

There are differences across fields in terms of affluent backgrounds: humanities scholars tend to be most likely to come from top SES quintile households. However, in all fields, most professors tend to come from families who earned above the median household incomes during their formative years.

Complementing these studies, others have found that roughly 80% of tenured and tenure-track faculty in the U.S. hail from a small number of elite schools, which themselves cater primarily to students from well-off families.

In short, no matter how you slice it, professors tend to be very sociologically distant from most other Americans — and this influences how we produce and disseminate knowledge, often in unfortunate ways.

However, to understand how we might close some of these gaps, we have to understand why they emerge and persist.

Pipeline Problems

Perhaps the primary way that institutions attempt to justify existing disparities, or a lack of progress in closing them, is to appeal to “the pipeline”: There just aren’t enough qualified applicants from underrepresented backgrounds for committees to draw from when they’re making hiring decisions.

One piece of data supporting these narratives is that there are significant differences in terminal-degree attainment along the lines of gender and ethnicity, as reflected in U.S. Census Bureau data:

A white American is roughly twice as likely to have a Ph.D. as a Black American, and four times more likely to hold a Ph.D. than an Hispanic American. A man is 33% more likely to have a Ph.D. than a woman, despite women significantly outpacing men for A.A., B.A., and M.A. degrees.

There are significant class disparities in Ph.D. attainment as well — doctoral candidates hail overwhelmingly, and increasingly, from relatively affluent families.

There are also systematic differences in the prestige of institutions that aspiring faculty from different backgrounds attend.

As a function of these disparities, jobs that require a Ph.D. — such as tenure-track professorships — will disproportionately exclude women, Blacks, and Hispanics, as well as people from less advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. These distortions would be amplified insofar as universities prefer to hire graduates of elite schools (which, again, they overwhelmingly do).

Systemic Bias

To be clear, the nonrepresentativeness of the professoriate is not, in itself, proof of injustice or wrongdoing. There is no reason to expect that any or all institutions will perfectly mirror broader societal base rates on every single dimension (gender, race, class, geography, ideology, etc.). Systemic variations in the occupations different groups choose can sometimes be the product of different cultures, values, lifestyles, life experiences, preferences, and priorities rather than parochialism.

However, significant over- or underrepresentation in highly coveted positions can be signs of opportunity hoarding, hostile work environments, and other forms of unjust discrimination. And within institutions of higher learning, there seems to be abundant evidence that many of the patterns observed in the chart above may not be benign or coincidental in nature.

For instance, even when we control for baseline levels of representation in the professoriate, we see that white, Asian, and male professors tend to be significantly overrepresented in tenured roles, while Black, Hispanic, indigenous, and female professors are overrepresented in nontenure eligible positions.

Critically, this IPEDS data on the gender and racial breakdown of the professoriate considers only faculty in full-time positions. Among full-time professors, women are in the minority. Looking at all faculty jobs, however, most postsecondary instructors are women — it’s just that women and minorities are especially likely to be hired into part-time roles. And irrespective of their rank or employment status, they tend to be concentrated into less prestigious and lower-paying schools (including two-year colleges) and in fields where faculty are not compensated as well.

And although they are less likely to secure tenure-line positions, even among tenure track professors, female and non-white faculty are also significantly more likely to be denied tenure or promotion as compared with white or male peers, and they’re less likely to receive counteroffers for the purpose of retention when they seek other jobs. They’re also more likely to resign.

Compared to male peers, female faculty are significantly more likely than men to exit of their own volition prior to retirement — largely due to insufficiently flexible demands, perceived hostile work environment or poor working conditions. Similar realities hold along racial and ethnic lines.

As a function of the fact that even many women and non-whites who do manage to secure tenure-line positions end up quitting or are pushed out prior to retirement, while men and whites tend to persist much longer in their tenure-stream roles, changing the gender composition of tenured professors is difficult. As a recent study in Science put it:

“A hypothetical cohort of new faculty hired at parity would fall to 48.2% women after 15 years, 45.4% after 25 years, and 40.6% after 35 years. In this cohort, it would take 21 years for half of men to leave their academic positions compared to only 17.5 years for women. By implicating attrition, these projections undermine claims that a lack of gender diversity among senior faculty is entirely due to slow demographic turnover and long career lengths among faculty.”

Moreover, in addition to differences in hiring, promotion, and retention, there are significant differences in pay across demographic lines. AAUP data reveal that female faculty members earn roughly 10 percent less than men at every rank, and 20 percent less than men overall (because women are especially likely to occupy lower ranks and teach at less prestigious schools). However, even looking within the same rank, field, and school system, female and minority faculty are often paid significantly less than white and/or male peers.

Likewise, conservative faculty, when hired at all, tend to be concentrated in less prestigious schools (even after controlling for factors like the school they graduated from or publication frequency and quality). Many conceal their political views and avoid working on controversial topics in order to avoid ideologically based discrimination and social sanctions (which can manifest in everything from hiring and promotion decisions, to peer review, to institutional review board decisions, and beyond).

That is, the distortions observed in the professoriate cannot be chalked up merely to “pipeline problems” or a lack of interest among various groups. Plenty of people from underrepresented populations are qualified to be, and interested in becoming, faculty members. They just aren’t being hired into full-time, tenure-track roles. Instead, insofar as they secure any kind of academic job, they are especially likely to be hired into contingent positions with far lower pay, few if any benefits, little job security, and virtually no institutional clout. Indeed, even as colleges and universities have been growing more ideologically homogeneous — more overtly and uniformly committed to social justice — they have also been growing more and more institutionally stratified, with systematic variance along the lines of race, gender, ideological leanings, and socioeconomic and/or regional background with regards to who gets sorted where.

Differential Rates of Change

While systematic biases in hiring, retention, and promotion contribute significantly to the disparities between the professoriate and the broader society, it is likely that even if these obstacles were eliminated, major imbalances would remain (as I explored with respect to ideological diversity here).

Indeed, many of the formal barriers preventing minority populations from entering academia and rising through the ranks have already been dismantled in recent decades. As a consequence, the professoriate is much more diverse in terms of race, gender, and sexuality than it was in the 1960s, or even the 1980s (although professors have grown significantly more ideologically homogenous over the same period).

The reason that American professors are not approaching parity with society despite these changes is that the broader society has been growing more diverse as well — and the rate of change in the professoriate is much slower than the rate of change in the demographics of America writ large. Hence, even as the faculty is becoming more and more diverse, the professoriate is not making much progress in matching the broader public.

Given these differential rates of change, the Nature Human Behavior study estimates that the professoriate would need to diversify at roughly 3.5 times its rate of change over the past decade in order to have a shot at approaching parity along the lines of race and gender by 2050. Ideology and socioeconomic background weren’t even factored into the analysis.

But even limiting ourselves to just these dimensions, diversifying the professoriate at 3.5 times the current rate would require dramatic changes in hiring, promotion, and retention. The study underlines explicitly that current approaches to DEI — assigning anti-bias training, appointing diversity officers, etc. — cannot plausibly lead the professoriate to parity anytime in the foreseeable future. The study does not provide a clear road map for what would plausibly get us there. But it’s worth thinking through that question a bit. For more on that topic, see my next essay.